Detroit Free Press Detroit, Michigan Sunday, October 27, 1957

Only 14, he's a chess whiz, but—

Though Brooklyn's Bobby Fischer amazes chess experts, his mother wants better report cards

by PAUL ABRAMSON

At 14, a local boy named Bobby Fischer is regarded as one of the 20 top chess players in the world. He is the U.S. Open Champion, has been invited to compete at tournaments in Russia and England. “Players with Fischer's ability” says Maurice Kasper, president of the Manhattan Chess Club, “come along only once in a century.”

Yet Bobby Fischer, a boy of exceptional intellect, is the despair of his high-school teachers. Last year, as a freshman, he fell behind in all his subjects, and almost didn't pass. This year the outlook isn't much better. Bobby is a chess whiz, but—

Just why mystifies everyone who knows him. “When he was 7,” says his sister Joan, 19, “Bobby could discuss mathematical concepts like infinity, or do all kinds of trick problems. But ask him to multiply two and two and he'd probably get it wrong.”

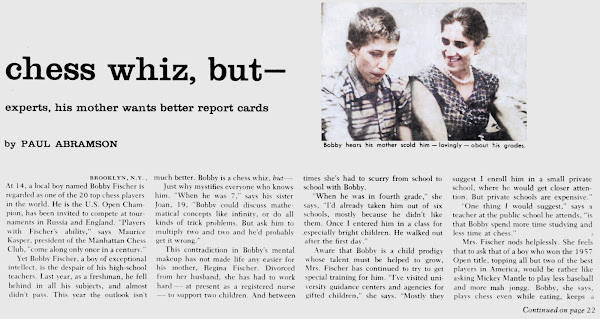

This contradiction in Bobby's mental makeup has not made life any easier for his mother, Regina Fischer. Divorced from her husband, she has had to work hard — at present as a registered nurse — to support two children. And between times she's had to scurry from school to school with Bobby.

“When he was in fourth grade,” she says, “I'd already taken him out of six schools, mostly because he didn't like them. Once I entered him in a class for especially bright children. He walked out after the first day.”

“Aware that Bobby is a child prodigy whose talent must be helped to grow, Mrs. Fischer has continued to try to get special training for him. “I've visited university guidance centers and agencies for gifted children,” she says. “Mostly they suggest I enroll him in a small private school, where he would get closer attention. But private schools are expensive.”

“One thing I would suggest,” says a teacher at the public school he attends, “is that Bobby spend more time studying and less time at chess.”

Mrs. Fischer nods helplessly. She feels that to ask that of a boy who won the 1957 Open title, topping all but two of the best players in America, would be rather like asking Mickey Mantle to play less baseball and more mah jongg. Bobby, she says, plays chess even while eating, keeps a board always near his bed to practice on.

Blond and on the thin side, Bobby away from chess is much like any teenager. He's wild about blueberry pie, the Dodgers, baseball, basketball and plaid shirts. He listens to rock 'n' roll records for hours on end. So far, he has shied away from girls and dancing.

$1 and a Rainy Afternoon

He's cocky about his chess. Once he played Samuel Reshevsky, the balding little accountant who's been the king of U.S. chess since 1936. The experienced Reshevsky, 46, polished off Bobby, then 13, with little trouble. But afterwards he told a bystander: “The boy is brilliant; he'll go far.” Bobby, meanwhile, was pointing out to anyone who would listen how Reshevsky had missed moves that would have ended the game sooner.

What amazes old chess hands is that Bobby has been playing the complex game less than eight years. His sister Joan had bought a $1 set to while away a rainy afternoon; she and her 6-year-old brother played a few games, but he was only mildly interested. Two years later he walked into the Brooklyn Public Library — he's a voracious reader — and saw Max Pavey, an international chess master, standing inside a rectangle and playing as many as 20 matches at once.

The curious Bobby sat down at a board and made a move. A few minutes later Pavey had forgotten about the other players and was concentrating hard on beating Bobby. He did, but it took him 15 minutes — a long time for an international master against an 8-year-old who'd player only a few games in his life.

A teacher of chess, Carmen Nigro, witnessed the game. Impressed, he offered to teach Bobby. Within a few years Bobby was beating Nigro regularly. By 1956, now a member of the Manhattan Chess Club, he had tied for fourth in the U.S. Open and won the National Junior Championship — the youngest titleholder in history.

This glittering record earned him a bid to the Lessing J. Rosenwald tournament, the top test of U.S. chess to which only six to 12 of the top players are invited. He was beaten several times — but, playing against the only man in the tournament to defeat Reshevsky, Bobby won.

“I never saw any game played better,” says referee Hans Kmoch. “It was the game of the century.”

Bobby finished eighth in the tournament, but won the coveted prize for brilliancy. Among those finishing behind him was Max Pavey, his library opponent of seven years earlier.

Last summer Bobby scored his greatest triumph, winning the U.S. Open Chess championship at Cleveland. He defeated the best American players with the exception of Reshevsky and Larry Evans, neither of whom competed. In the next few months, some experts believe, Bobby may prove himself the equal of them both.

Money for His Mother

Right now, though, he must start doing better in his school work and try to help out his hard-working mother. To make money, he has taken on as many as 30 challengers simultaneously at $1 a challenger. But such games, he says, “don't produce good chess. They're just hard on your feet.”

Recently his chess playing has started to produce bigger dividends. He won $750 for winning the Open, $125 in another tournament. This, he says, will help him toward his goal: the chess championship of the world.

How long will it take him? Says the cocksure Bobby about a crown that some men have spent a lifetime chasing: “I guess maybe 10 years.”

— Parade, October 27, 1957